Diving across bridges

Kernel code is seldom documented, even for Linux, which is the Unix-like most known Operating System.

While guides aimed at several configurations and tweakings are available, when it comes to kernel internals the naked code is left alone to speak (and hopefully to explain something) to the reader. It is maybe a laziness act: after the effort of understanding code, you really don’t want to spend more work to make it comprehensible to others, or to yourself in the future. But this is a sort of counterproductive behaviour.

The most famous *BSD Operating Systems have a monolithic kernel, whose drivers are included inside the source code and are compiled within the whole kernel structure. Some drivers can be obviously kept away, by using the machine description file in an appropriate way: it is usually located in

/usr/src/sys/arch/<arch_name>/conf/FILE

where FILE is the type of kernel to be compiled. Usually, the GENERIC kernel is used; if the architecture is amd64, the file will be

/usr/src/sys/arch/amd64/conf/GENERIC

The directory usr/src/sys/dev contains information and subdirectories about all the types of devices the kernel is able to deal with. Drivers for a particular type of device are stored in the related subdirectory.

Let’s take as an example a system which hosts the Intel PRO/Wireless 2100 MiniPCI network adapter. Apropos can be used to find the relevant pages in the manual as regards this device:

$ apropos "Intel PRO/Wireless 2100"

ipwctl (8) configure Intel PRO/Wireless 2100 network adapter

configure Intel PRO/Wireless 2100 network adapter

ipw (4) Intel PRO/Wireless 2100 IEEE 802.11 driver

DESCRIPTION The driver provides support for the Intel PRO/Wireless 2100 MiniPCI network adapter. The Intel firmware requires acceptance of the End User License Agreement. The full license text can be found in /libdata/firmware/if_ipw/LICENSE. The license is...

pci (4) introduction to machineindependent PCI bus support and drivers

...fpa DEC DEFPA FDDI interfaces. fxp Intel EtherExpress PRO 10+/100B Ethernet interfaces. gsip...and PRISM-II 802.11 wireless interfaces. wm Intel i8254x Gigabit Ethernet driver. Serial...QLogic ISP-1020, ISP-1040, and ISP-2100 SCSI and FibreChannel interfaces. mfi LSI...

As it is printed out, ipw(4) represents the driver itself (which is always located in Section 4 of the Manual). It is presented as a MiniPCI device, so a file whose name includes ipw has to be found in the pci subdirectory of usr/src/sys/dev. It is the C file if_ipw.c, as it is written inside the file itself after the Copyright note:

#include <sys/cdefs.h>

__KERNEL_RCSID(0, "$NetBSD: if_ipw.c,v 1.63 2017/02/02 10:05:35 nonaka Exp $");

/*-

* Intel(R) PRO/Wireless 2100 MiniPCI driver

* http://www.intel.com/network/connectivity/products/wireless/prowireless_mobile.htm

*/

Note that this may not be the only file of the driver. Often, other header files can in fact be required: in this case, for example, if_ipwreg.h and if_ipwvar.h (in addition to all the code files #included in them).

When dealing with network adapters, the driver source code is often stored in an if_<name>.c file. But this is not always the case for other types of devices.

As documented in driver(9), each NetBSD driver should at least implement four functions, to let the system autoconfigure when a device has to be found and used. They are related to the following operations: match, attach, detach, activate. There can be cases when even some of these fundamental four ones are not implemented (as for detach, for example).

Nowadays, almost only PCI Express devices are used in motherboards. It is anyway backward-compatible with PCI and from the software perspective almost nothing changed since the PCI era. In NetBSD, all the devices are arranged in a tree-structure, where each node has a parent node, and root is the global parent. First of all, all the children of the root node can be shown with drvctl(8):

$ drvctl -l

root swcrypto0

root mainbus0

root pad0

The most relevant child node here is mainbus0: it contains most of the system devices. They can be listed with:

$ drvctl -lt mainbus0

ioapic0

cpu0

acpicpu0

coretemp0

cpu1

acpicpu1

coretemp1

acpi0

hpet0

acpiec0

acpiwmi0

acpivga0

acpiout0

acpiout1

acpiout2

acpiout3

acpidalb0

acpidalb1

attimer1

pckbc1

pckbd0

wskbd0

pms0

wsmouse0

pckbc2

acpiacad0

acpibat0

acpibut0

acpilid0

acpitz0

pci0

pchb0

agp0

ppb0

pci1

radeon0

radeondrmkmsfb0

wsdisplay0

hdaudio0

hdafg0

uhci0

usb0

uhub0

uhidev0

ums0

wsmouse1

uhci1

usb1

uhub1

uhci2

usb2

uhub2

ehci0

usb3

uhub4

hdaudio1

hdafg1

audio0

spkr0

ppb1

pci2

iwn0

ppb2

pci3

ppb3

pci4

uhci3

usb4

uhub5

uhci4

usb5

uhub6

uhci5

usb6

uhub3

ugen0

ehci1

usb7

uhub7

umass0

scsibus0

sd0

uvideo0

video0

umass1

scsibus1

sd1

ppb4

pci5

fwohci0

ieee1394if0

fwip0

sdhc0

sdmmc0

ichlpcib0

tco0

isa0

pcppi0

spkr1

midi0

sysbeep0

ahcisata0

atabus0

wd0

atabus1

atapibus0

cd0

atabus2

atabus3

ichsmb0

iic0

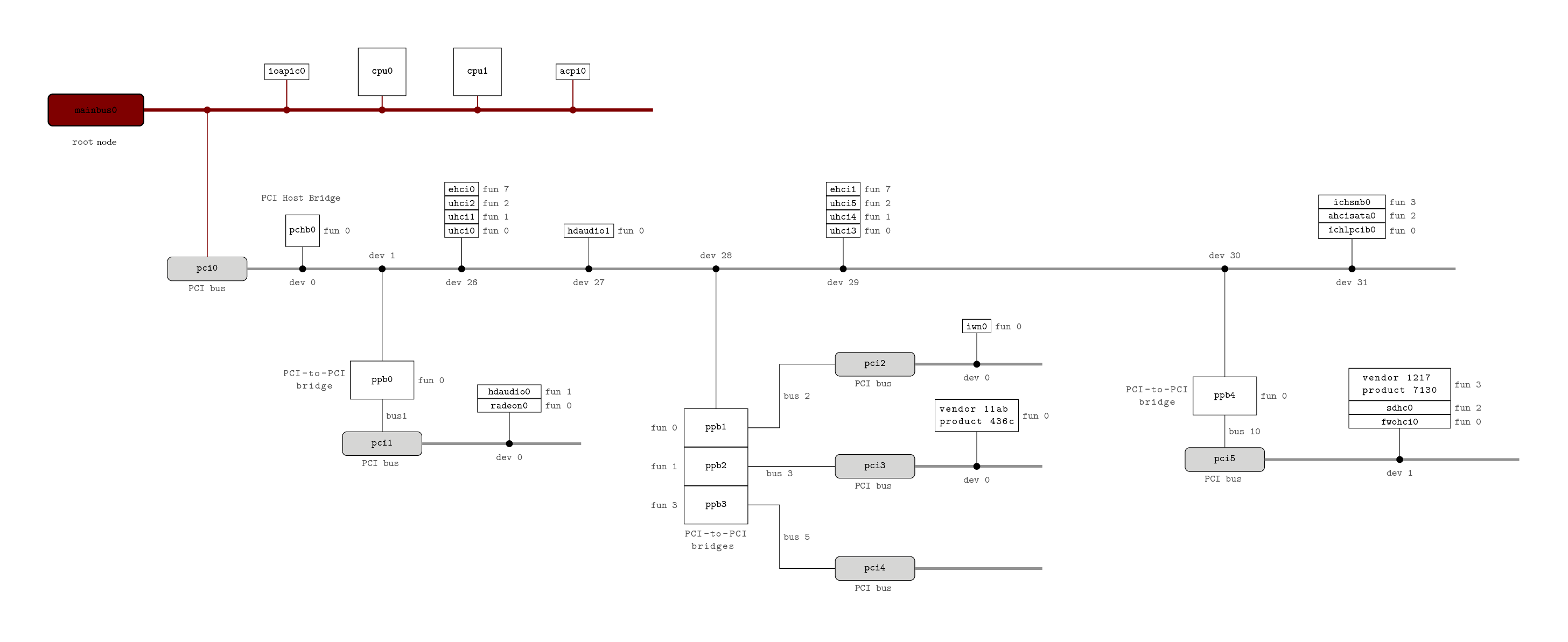

This is a laptop collection of devices, showing how the kernel has learnt about the hardware. It depends both on the kernel code and on the way the devices presented themselves to the OS. This is a logical structure, which does not necessarily mirror the physical arrangement of the devices. For example, different PCI-to-PCI bridges can be implemented all inside a single chip. The PCI buses themselves could not correspond to physical buses on the motherboard: they could simply be an abstraction (made by the kernel, or by the devices firmware) which offers a more convenient way to handle the underlying hardware. Regardless of the reality, this logical structure is significant because when the kernel will refer to hardware, it will refer to this arrangement.

Let’s focus on PCI: a simple hierarchy is shown below, with 6 PCI buses linked by bridges. It includes traditional PCI and new PCI Express devices, but they are all nodes of a standard PCI hierarchy. In particular,

pci0

pchb0

agp0

ppb0

pci1

...

...

ppb1

pci2

...

ppb2

pci3

ppb3

pci4

...

ppb4

pci5

...

Note that pci0 is the main PCI bus of the system. It contains the PCI host bridge (it won’t be considered now) and several other devices. Bridges are a particular kind of device that can connect a PCI bus to another one: they are highlighted here, together with their children buses. All the five bridges ppb{0,4} lie in the pci0 bus, so the buses are arranged in just two hierarchical levels, the upper level being represented by pci0 and the lower level being represented by the peers pci{1,5}.

The PCI bus and the PCI-to-PCI bridges themselves need a driver: their source files are located in the directory of the previous example, /usr/src/sys/dev/pci. The driver main file for the PCI bus is simply named pci.c, for the PCI-to-PCI bridges it is ppb.c. Note that each actual device is considered as a driver instance: its name is composed by the driver name, followed by a number. So, the first PCI bus found by the kernel is pci0, the first PCI-to-PCI bridge found is ppb0 and so on.